The Men and Women of Chishti and Inayati Sufism[1]

Netanel Miles-Yépez

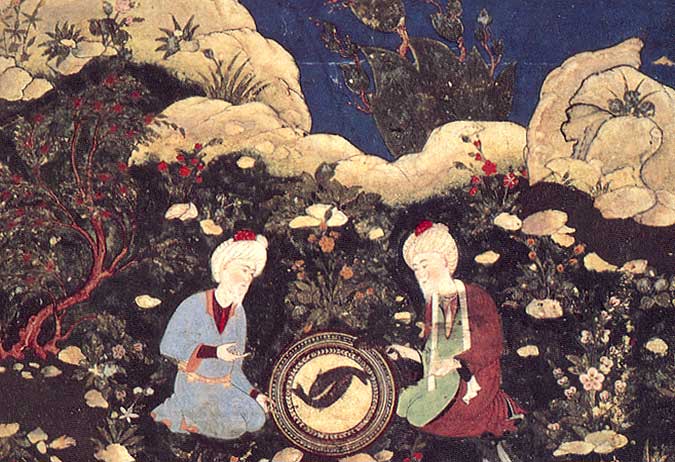

The prophets Elias and Khadir at the fountain of life, late 15th century. Timurid period. Herat, Afghanistan.

The silsila or ‘chain’ of transmission of a lineage is of central importance to the Sufi path. It is understood to be a conduit of the baraka or spiritual blessing of any genuine Sufi school. It links the murids of an order with the combined spiritual power of their mystical forebears, and with the unseen transformative forces that transpire behind the outward manifestation of this chain or pedigree.

The silsila is recited on various occasions, most often before group zikr. It is also an important part of the practice known as tasawwur-i murshid, in which one works one’s way backward through the lineage, connecting with each name or link in the chain, establishing a relationship with each as a spiritual ancestor. In this way, it is likewise connected with Sufi initiation, bay’ah, during which it is also sometimes recited. The Arabic word bay’ah refers to a covenant sealed by ‘taking hand’ with another, as the initiate takes the right hand of the Sufi master, a hand that took the hand of the master before, down through the centuries in an unbroken chain. In so doing, the new murid may come to realize that this is the hand that took the actual hand of another master—whose name, though now famous or even legendary—was nevertheless a real person on the path. This gives the murid confidence in what is possible for a human being to achieve.

The Chishti-Nizami-Kalimi Lineage

The silsila of Hazrat Pir-o-Murshid Inayat Khan (1882–1927) is that of the Chishti-Nizami-Kalimi lineage, which he inherited from his master, Sayyid Abu Hashim Madani (d. ca.1907), each of the three names—Chishti-Nizami-Kalimi—marking a milepost within the lineage, or signaling an important emphasis often associated with a person or a place.

Chishti Sufis derive their name from Chisht, a small town in eastern Khurasan (now Afghanistan) near Herat. Sometime in the 10th-century, Khwaja Abu Ishaq Shami (d. 940) was directed by his master, ‘Ulu Dinwari in Baghdad, to travel to the far outpost of Chisht, where he initiated a disciple, Khwaja Abu Ahmad Abdal Chishti (d. 966), beginning a succession of masters associated with that humble town.[2] The story told in the lineage of this first Chishti initiation is an interesting one.

Having traveled to Chisht at the direction of his master, Khwaja Abu Ishaq is first befriended by Ukht Farusnafa, the ‘sister of Farusnafa,’ who we might call the mother of the Chishtis. A saintly woman of the royal family, the two soon developed a deep spiritual connection.

One day, Khwaja Abu Ishaq confided to his friend, Ukht Farusnafa, that her brother, Emir Farusnafa and his wife would soon have a child. The child he saw would grow up to be a great Sufi; but only if she helped to raise him, imbuing him with her own spiritual blessing. Otherwise, the dissolute ways of his father, the prince, and the temptations of wealth and power, would influence him to evil.

Ukht Farusnafa did as she was asked and became a second mother to her nephew and brother’s heir, instilling him with virtues his father did not possess. Over time, he grew into a noble young prince.

One day, while he was out on horseback with a hunting party, he became separated from the others and his horse soon happened upon a circle of ten Sufis engaged in zikr. So struck was he by the sight of these holy beings, and the power radiating from their remembrance of God, that he immediately dismounted and prostrated before them, asking to be admitted to the circle. The leader, Khwaja Abu Ishaq, smiled and initiated Abu Ahmad Abdal Chishti, the nephew of his spiritual sister and his long awaited successor.[3]

The Central Asian character of the early Chishti lineage is suggested by use of the title khwaja for a number of the early masters of the lineage. Unlike the more familiar titles, shaykh or pir (meaning, ‘elder’) used in other regions, the title khwaja (‘master of wisdom’) was preferred in Khurasan.[4] Thus, even Mu‘in ad-Din Chishti, who brought the Chishti lineage into India, where it took on its distinctive character, was called Khwaja Mu‘in ad-Din, as were the four masters who followed him.

Khwaja Mu‘in ad-Din (d. 1236) was the disciple of Khwaja ‘Usman Harvani (d. 1210), with whom he traveled and served for twenty years, before setting his sights on India late in his life.[5] A story of Khwaja Mu‘in ad-Din’s preaching in India (sometimes told of his master, Khwaja ‘Usman Harvani, who did not travel to India) is both entertaining and instructive:

Once in India, Khwaja Mu‘in ad-Din quickly attracted thousands of followers, all good Muslims who seemed to be loyal and devoted disciples. But one day, as he was looking out over the masses of them, he suddenly felt he had had enough of all the pomp and said in a voice just loud enough for others to hear, “I think I’ve changed my mind.”

Someone who heard him asked, “Master, about what have you changed your mind?”

“Perhaps,” he said, “the Hindus are right, after all . . . I think I must serve the goddess Kali now and make obeisance to her.”

The disciple gasped and word quickly spread through the crowd, “The master has become a Hindu and intends to serve the black goddess, Kali!”

Immediately, scores of disciples abandoned him, while others waited to see what he would do next.

Seeing that some disciples still remained, Khwaja Mu‘in ad-Din turned in the direction of the local Kali mandir (temple) and started to walk.

Seeing this, the remaining disciples deserted him, saying: “How can children of Allah, the formless God, worship the goddess Kali? It is against his own teachings!”

But as he was walking toward the Kali mandir, Khwaja Mu‘in ad-Din noticed that there was actually one disciple who still remained with him, and he smiled secretly. He was glad to be rid of the others, but if this one had gone, it would have been a real loss. Nevertheless, he continued on toward the temple, thinking about the fickleness of human nature and how quickly the others had departed. He began to pray to as he walked, saying—“God! God! What are human beings that you should notice them, when they fail to recognize you in every face before them? You are all and everything!” And with these words, he fell into ecstasy, falling prostrate on the very the steps of Kali’s temple, facing the statue of Kali!

After he came to, he realized that it must have appeared as if he had made obeisance to Kali, and he said to his only remaining disciple, who was then kneeling beside him and mopping his forehead—“Why do you stay when all the others have left? They’re all good Muslims, and there are many learned scholars among them; perhaps you too should go before you are polluted by contact with me.”

But the disciple replied, “Mawla—master—it was you who taught us that nothing exists except God. If that is true, then Kali is not Kali, and this temple and all of its images are nothing other than divinity. So what does it matter whether you bow to the East or West, to the earth or the heavens? If nothing exists but God, then there is nothing before whom to bow except God, even if one seems to be bowing before Kali.”

Then Khwaja Mu‘in ad-Din embraced him, and the two departed together. This disciple became his successor, the famous ecstatic, Khwaja Qutb ad-Din.[6]

Khwaja Mu‘in ad-Din was called Gharib Nawaz, the ‘sultan of the poor,’ and today, his dargah or burial shrine in Ajmer is one of the most important pilgrimage sites in all of India, where thousands of the poor are fed. And yet, it is not Khwaja Mu‘in ad-Din’s name that is referenced in the trilogy of lineage markers—Chishti-Nizami-Kalimi—but that of Khwaja Nizam ad-Din Awliyya (d. 1325), under whom the new Indian form of Chishti Sufism reaches its apogee.

Khwaja Nizam ad-Din, called Mahbub-i Ilahi, ‘beloved of God,’ presided over a court like an ascetic king. Each day, he had hundreds of visitors who left donations, which he would then distribute entirely to the poor before retiring at night. Though a wonderful story is also told of a day when he had nothing to give.

Khwaja Nizam ad-Din’s most beloved disciple was the poet, Amir Khusraw, who served in the court of the Sultan. Once it happened that Amir Khusraw was returning to Delhi after doing some business elsewhere, and stopped to rest at a caravanserai, or inn, where he met a man who had just come from Delhi. The man was a farmer who had gone to Delhi after a drought had left him and his family impoverished, hoping that the great saint of Delhi, Khwaja Nizam ad-Din, would help him. Khwaja Nizam ad-Din always gave whatever he had, but it happened that on that day, no donations had been received, so nothing could be given. But Nizam ad-Din could not bear to turn the farmer away empty-handed, so he gave the barefoot farmer his own sandals, which he had received from his master, Baba Farid. The farmer, who had hoped for money or food, accepted the sandals with a quiet disappointment.

Later, when the farmer encountered Amir Khusraw and recounted these events, the poet’s eyes lit up and he exclaimed, “Do you mean to say that you are in possession of the holy sandals of Khwaja Nizam ad-Din?”

The farmer produced the sandals, and Amir Khusraw immediately produced a chest of gold, and offered to trade. The farmer was beside himself with happiness, and so was Amir Khusraw.

A few days later, Amir Khusraw arrived in Delhi, bearing Khwaja Nizam ad-Din’s sandals on his head.

Khwaja Nizam ad-Din asked, “How much did you pay for those sandals?”

“All that I possess,” he replied.

And Khwaja Nizam ad-Din said with a smile, “You bought them cheaply!”[7]

Khwaja Nizam ad-Din was the twentieth master in the lineage after the prophet Muhammad, peace and blessings be upon him. In the thirtieth generation came Shah Kalim Allah Jahanabadi (1650-1729), a grandson of the architect of the Taj Mahal and Lal Qila, who himself would become one of the great architects of the lineage, initiating a “renaissance” in Chishti Sufism.[8]

A resident of Delhi, Shah Kalim Allah’s home near Lal Qila, the famous ‘Red Fort,’ became the principle seat of the Chishti lineage in the Mughal Period. A gifted intellectual and leader, he sought “to reunify the many regional Chishti centers and emphasize the core teachings of the original Chishti lineage.”[9]

One aspect of this reunification and revival was achieved through his writings, such as his classic work, Kashkul-i Kalimi, ‘The Alms-bowl of Kalim Allah,’ in which he gathered and collected teachings on meditation and contemplation from numerous Sufi masters for the benefit of his students and future Sufis of the Chishti lineage.[10]

But Shah Kalim Allah also seems to have been unusually broad-minded; for unlike many Sufi masters, he initiated both men and women, Muslims and non-Muslims alike.[11] And despite his abiding commitment to the Chishti lineage (to which he gave primary allegiance), he actually carried the transmission of all four of the early schools of Sufism—Chishti, Naqshbandi, Qadiri, and Suhrawardi—and thus, the Kalimi lineage which stems from him, has sometimes been called the lineage of “Four-School Sufism.”[12]

The four schools had begun their unification with the Chishti-Nizami master, Shaykh Mahmud Rajan (d. 1495), who also carried the Suhrawardi transmission, and was continued by Shaykh Hasan Muhammad (d. 1575), who carried the Qadiri transmission, until finally being unified by Shah Kalim Allah, as a carrier of the Naqshbandi transmission.[13] Thus, it was a characteristic of masters within the Kalimi lineage to emphasize training in the teachings and practices of all four schools.

Shah Kalim Allah himself had directed his successor, Shaykh Nizam ad-Din Awrangabadi (d. 1730), to emphasize the teaching of whichever school might best suit those to whom he was guiding; for he recognized that the needs of the seeker are paramount, and each must be given the particular nourishment they require.[14]

Almost two hundred years later, Hazrat Inayat Khan would confirm this emphasis of the Kalimi lineage, writing in his Confessions of the training he had received from his own master, Sayyid Abu Hashim Madani:

I studied the Qur’an, Hadith, and the literature of the Persian mystics. […] After receiving instruction in the five different grades of Sufism, the physical, intellectual, mental, moral, and spiritual, I went through a course of training in the four schools: the Chishti, Naqshbandi, Qadiri, and Suhrawardi.[15]

The Four-School Sufism of Shah Kalim Allah, and his open attitude toward the initiation of women and non-Muslims, would in time become foundational aspects of Hazrat Inayat Khan’s universalist Sufism.

The Women of the Chishti Lineage

The thirty-seven names and lives that comprise the traditional Chishti-Nizami-Kalimi silsila, or chain of transmission—beginning with the prophet Muhammad, peace and blessings be upon him, and ending with Hazrat Inayat Khan—span almost 1,400 years of spiritual blessing. Some of the names, like Hasan of Basra (d. 728), Ibrahim ibn Adham (d. 779) and Mu‘in ad-Din Chshti (d. 1236), are famous among all Sufis, their sayings and deeds recorded in classic texts and remembered throughout the Sufi world. Some, like Qutb ad-Din Bakhtiyar Kaki (d. 1235), Farid ad-Din Ganj-i Shakar (d. 1265), Nizam ad-Din Awliyya (d. 1325), and Nasir ad-Din Chiragh-i Delhi (d. 1356), are more famous within the Chishti lineage. And some names are so obscure, even within the lineage, that we know almost nothing verifiable about them.

Sadly, we know even less about the many women who have influenced the lineage. And yet, we live in a time that demands a more balanced perspective. If the silsila is meant to connect us with the flow of blessing in our tradition, and to inspire confidence in it, we must see ourselves represented in it, women as well as men.

For many women, the silsila is no longer inspiring. A long list of exclusively male names, however great and holy, is not necessarily meaningful to the many gifted women who often make up the majority of universalist Sufi circles today. The message, whether intentional or merely the inertial effect of historical patriarchy, is one of exclusion. “Where are the women?” we hear; which is another way of saying, “Where do I fit in this tradition?”

One answer is that women have always been present in Sufism, which is true. Accounts of women saints are found throughout Sufi literature; indeed, many of them are found in the writings of one the greatest Sufi masters, Muhyiddin ibn ‘Arabi (1165-1240), as he describes the great women Sufis with whom he learned in Andalusia.[16] Likewise, in the 17th-century, the famous Sufi Mughal prince, Dara Shikuh (1615-1659), included a section on “wise, virtuous, perfected, and united” women in his Safinat al-Awliya’, ‘ship of saints.’[17] And few Sufis are more acclaimed than Rabi‘a al-Adawiyya of Basra, who is credited by most as changing the emphasis of Sufism toward divine love.[18]

But even the great Rabi‘a of Basra is not included in any Sufi silsila, and her example, though profound, is but one shining exception among hundreds of male saints. So where are the women, we ask again? The answer is uncomfortably obvious—silent and silenced by patriarchal culture, buried in the footnotes of history. The vast majority of women throughout Sufi history have not had the same opportunity for spiritual pursuits as men, and even when they did, they were often illiterate and their sayings rarely recorded by their male counterparts. Those who were literate, usually belonging to the most privileged classes, existed in another type of cage, like Princess Jahanara, the sister of Dara Shikuh, who was not allowed by precedent or prejudice to inherit the lineage of her male teacher, even though he wished it.[19]

With few exceptions, that was simply the reality. But there is nothing to say that we need to be satisfied with that reality. In recent years, many have begun the work of reclaiming the legacy of Sufi women, in general.[20] For the women of the Chishti lineage, we can do the same; though it is difficult work, and often the results yield less of a picture of these women than we might desire. And yet it must be done.

It requires a deep knowledge of the Chishti literature, and an ability to access the historical sources. Today, the foremost expert in the history of the silsila, and the sources of information regarding it, is our own beloved companion on the path, Pir Zia Inayat-Khan—Sarafil Bawa. In two separate works, he has given us the gift of an otherwise unobtainable portrait of the Chishti lineage in the English language: a scholarly treatment in “The ‘Silsila-i Sufian’: From Khwaja Mu‘in al-Din Chishti to Sayyid Abu Hashim Madani,” found in the edited volume, A Pearl in Wine: Essays on the Life, Music and Sufism of Hazrat Inayat Khan; and a less formal oral presentation of Chishti lore, edited by us both, in Tree of Lights: The Chishti Lineage of Hazrat Inayat Khan.[21]

Through these works, the wisdom of generations of Sufis in the Chishti-Nizami-Kalimi silsila has become accessible to English speaking Sufis, and we begin to see the faces of women connected with the silsila peeking through the latticework of history, some playing prominent roles in the shaping of the lineage.

Sometimes, we do not know their names. The are simply—Ukht Farusnafa, ‘sister of Farusnafa,’ who we have already called the “mother of the Chishtis”; Umm Abu Muhammad, the ‘mother of Abu Muhammad,’ who received his first teachings in Sufism from her, “a woman of extraordinary insight and wisdom”;[22] Zawja Bakhtiyar Kaki, ‘wife of the One Who is Fortunate in Bread,’ who is connected with a miracle;[23] or Ukht Chiragh-i Dehli, the ‘sister of the Lamp of Dehli,’ the sister and mother of Chishti masters.[24]

But many names are known—names like, Bibi Safiya, Bibi Amat al-Ghani, Sayyid Begum, or Muhtarima Pot Begum Sahiba. The words bibi, muhtarima, and sahiba are titles of respect, generally meaning, ‘lady.’ And begum is a married woman of high rank. Though, in many cases, we know little more of them than their relationship to one of the lineage masters, or for instance, that Shaykh ‘Ilm ad-Diin’s mother, Bibi Safiya, was a granddaughter of a Sufi saint called “The Ocean-Drinker,” and was herself “A soulful woman possessed of unique powers of insight.”[25]

In another class are those who, whether their names are known or not, play a significant part in a story or anecdote in the lineage, or are themselves Sufis of note. These include—Bibi Hafiza Jamal, the daughter of Khwaja Mu‘in ad-Din, who had memorized the entire Qur’an, and who was so gifted spiritually, that her father actually made her one of his successors;[26] Bibi Zulaykha, the saintly mother of Khwaja Nizam ad-Din, of whom it is said, “Every month when the Shaykh saw the new moon, he offered felicitation to his mother by placing his head at her feet,” and whenever he had a problem after her death, went to pray at her grave;[27] and Bibi Fatimah Sam, a great Sufi saint of Dehli.

The latter was revered by both Khwaja Farid ad-Din and Khwaja Nizam ad-Din. When discussing the place of women saints in Sufism, and talking about Bibi Fatimah Sam, Khwaja Nizam ad-Din said, “When a wild lion comes into the city from the forest, who asks whether it is male or female?”[28] He even told stories of her on more than one occasion and quoted verses attributed to her:

For love you search, while still for life you strain.

For both you search, but both you can’t attain.[29]

Ultimately, love leaves no room for the self, says Bibi Fatimah Sam.

And then there are the great ladies of Islam and Sufism who are connected with the Chishti lineage—Khadijah al-Kubra, ‘A’ishah Umm al-Mu‘min, and Umm Salama, the wives of the Prophet Muhammad; Fatimah az-Zahra, the daughter of the Prophet; Rabi’a al-Basri, who changed the course of Sufism; and Shahzadi Jahanara Begum Sahiba (1614-1681), the daughter of the Mughal emperor, Shah Jahan.

Though a disciple of a Qadiri master, Mulla Shah, Princess Jahanara later had a profound mystical experience while on pilgrimage at the burial shrine of Khwaja Mu‘in ad-Din Chishti (on whom she wrote a biography), ‘taking hand’ with the sainted Chishti master in the inner world some four centuries after his death.[30] She is buried near the dargah of Khwaja Nizam ad-Din, and upon her simple marble marker is written:

He is the Living, the Sustaining.

Let no one cover my grave except with greenery,

For this grass suffices as a tomb cover for the poor.

The annihilated faqir Lady Jahanara,

Disciple of the Lords of Chisht,

Daughter of Shahjahan the Warrior

(may God illuminate his proof).[31]

The Integrated Shajara Sharif ‘Inayati

As we have seen, the silsila traces initiatic ancestry from one master to another, rather than the full flow of baraka or spiritual blessing from all of the figures, male and female, that have influenced its direction and development. If we would see something of this greater influence, we must look to the shajara of the lineage.

The graphic representation of the silsila is called the shajara sharif, or ‘noble tree.’ The shajara of Hazrat Pir-o-Murshid Inayat Khan is the Shajara Sharif ‘Inayati. This tree traces the Chishti-Nizami-Kalimi lineage imparted to him by his master before his passing. The addition of ‘Inayati marks his own contribution as the opener of the way of universalist Sufism.

Although the shajara sharif is usually a simple linear list of the names of the silsila masters, there is no necessity of its being limited to this simple form. In the shajara, we have the possibility of seeing more complexity. The silsila may be fixed in the historical reality of how the lineage was passed from one male master to another, but the shajara can show us the missing women of the lineage, filling out the leaves and branches that would illustrate its full majesty.

Of course, we must acknowledge the fact that, according to historical circumstances beyond our control, or even the control of those who came before us, the silsila was forged and passed on in the form it was, from one male successor to another for nearly 1,400 years. But we can also begin to acknowledge the women who influenced and impacted the lineage through the centuries in our shajara, doing what we can to reclaim their legacy of service and sacrifice, adding their names to the ancestral tree of the lineage.

Thus, a new, integrated Shajara Sharif ‘Inayati has been created to bring the men and women of the lineage together for the first time.

Hazrat Inayat Khan himself said, “I see as clear as daylight that the hour is coming when woman will lead humanity to a higher evolution.”[32] And still more significantly, he granted the rank of murshid to only four disciples in his lifetime, all of them women: Murshida Rabia Martin (1871-1947), Murshida Sharifa Goodenough (1876-1937), Murshida Sophia Saintsbury-Green (1866-1939), and Murshida Fazal Mai Egeling (1861-1939). But for various reasons, none of these women have ever been represented in the shajaras of the many lineages of universalist Sufism. However, today we must acknowledge their place as the mothers of universalist Sufism who preceded and gave their blessing to all the lineage masters who came after them.

For this reason, the integrated Shajara Sharif ‘Inayati gives them their proper place beneath the name of Hazrat Pir-o-Murshid Inayat Khan, prior to the branching of the universalist Sufi lineage into its many current expressions.

Notes

[1] An edited version of a talk given at a Naropa University Sufi Retreat Intensive, January 11th, 2017, and a more developed talk, explicitly proposing a new, integrated Shajara Sharif ‘Inayati at the following year’s Sufi Retreat Intensive, January 9th, 2018.

[2] Carl W. Ernst, and Bruce B. Lawrence. Sufi Martyrs of Love: The Chishti Order in South Asia and Beyond. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002: 19-20.

[3] Zia Inayat-Khan. Tree of Lights: The Chishti Lineage of Hazrat Inayat Khan. Richmond, VA: The Inayati Order, [Forthcoming]: 29-30.

[4] Ernst, Sufi Martyrs of Love, 19.

[5] As reported in the traditional hagiographies. See Ernst, Sufi Martyrs of Love, 149.

[6] See Inayat Khan. The Sufi Message: Volume X: Sufi Mysticism. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1990: 64-66.

[7] See Inayat-Khan, Tree of Lights, 57-58.

[8] Ibid., 87. K.A. Nizami. “Chishtiyya.” Encyclopedia of Islam. (Vol. 2). Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1960: 55.

[9] Scott Kugle (ed.). Sufi Meditation and Contemplation: Timeless Wisdom from Mughal India. Trs. Scott Kugle and Carl Ernst. New Lebanon, NY: Suluk Press, 2012: 18.

[10] Published in English translation in Kugle, Sufi Meditation and Contemplation, 18.

[11] Ernst, Sufi Martyrs of Love, 142. Kugle, Sufi Meditation and Contemplation. 18.

[12] Ernst, Sufi Martyrs of Love, 142-43.

[13] Ibid., 142-43, 128-29.

[14] Ibid., 28. Kugle, Sufi Meditation and Contemplation, 31-32, and Pir Rasheed-ul-Hasan Kaleemi’s preface, xii.

[15] Inayat Khan’s “Confessions” in Inayat Khan. The Sufi Message: Volume XII: The Divinity of the Human Soul. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1990: 149. Even the revered modern Chishti master, Pir Rasheed-ul-Hasan Jeeli-ul-Kaleemi (d. 2013), has written that the Kalimi branch of the Chishti lineage combined the four schools of Sufism “into one path, trying to take the best of each.” Kugle, Sufi Meditation and Contemplation, xiv.

[16] Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi. Sufis of Andalusia: The Ruh al-Quds & al-Durrat at-Fakhirah. Tr. R.W. J. Austin. Roxburgh, Great Britain: Beshara Publications, 2002.

[17] Ernst, Sufi Martyrs of Love, 50.

[18] Annmarie Schimmel. Mystical Dimensions of Islam. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1975: 38.

[19] Annmarie Schimmel. My Soul is a Woman: The Feminine in Islam. New York, NY: Continuum, 1997: 50.

[20] In recent years, many have begun the work of reclaiming the legacy of Sufi women in general. Shaykh Javad Nurbakhsh has given us a work on Sufi Women, Shaykha Camille Helminski has written Women of Sufism: A Hidden Treasure, and Tamam Kahn has written Untold: A History of the Wives of Prophet Muhammad.

[21] Although the title, Tree of Lights: The Chishti Lineage of Hazrat Inayat Khan, bears resemblance to the title of the nineteenth-century book of Chishti hagiography, Shajarat al-Anvar, which has the same meaning, that book has never been translated and exists only in manuscript. The material in Pir Zia’s small book is original and not a translation of the former work. It was been transcribed from oral talks by Pir Zia (ca. 2000), and was originally edited for a private publication and made available to murids in 2001. Recently, it was re-edited by myself and Pir Zia so that Inayati murids may once more have the benefit of accessing this information and studying their own lineage.

[22] Inayat-Khan, Tree of Lights, 30-31.

[23] See Basira Beardsworth. Chishti Sufis of Dehli in the Lineage of Hazrat Pir-o-Murshid Inayat Khan. Private publication, 2013: 11.

[24] Inayat-Khan, Tree of Lights, 69.

[25] Zia Inayat Khan. “The ‘Silsila-i Sufian’: From Khwaja Mu‘in al-Din Chishti to Sayyid Abu Hashim Madani,” A Pearl in Wine: Essays on the Life, Music and Sufism of Hazrat Inayat Khan. Ed. Zia Inayt Khan. New Lebanon, NY: Omega Publications, 2001: 292.

[26] Inayat-Khan, Tree of Lights, 6.

[27] K.A. Nizami. “Introduction.” Morals for the Heart: Conversations of Shaykh Nizam ad-din Awliya Recorded by Amir Hasan Sijizi. Nizam ad-Din Awliya. Tr. Bruce B. Lawrence. New York, NY: Paulist Press, 1992: 19-20.

[28] Paraphrase of Nizam ad-Din Awliya, Morals for the Heart, 103.

[29] Ibid., 354.

[30] Carl E. Ernst (ed.). Teachings of Sufism. Boston, MA; Shambhala Publications, 1999: 194-99.

[31] Ernst, Teachings of Sufism, 194-95.

[32] Inayat Khan. Biography of Pir-o-Murshid Inayat Khan. London: East-West Publications, 1979: 243.